Our Black History

By Sally J. Ling

In honor of Black History Month, we present three stories that illustrate pieces of our local past.

Some interviews for this piece were taken from those conducted through Project History, a cooperative effort of the Deerfield Beach Historical Society and the Communications and Broadcast Arts magnet program at Deerfield Beach High School.

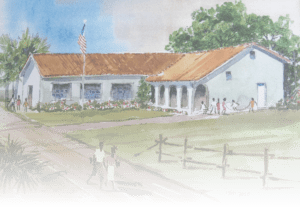

Braithwaite School

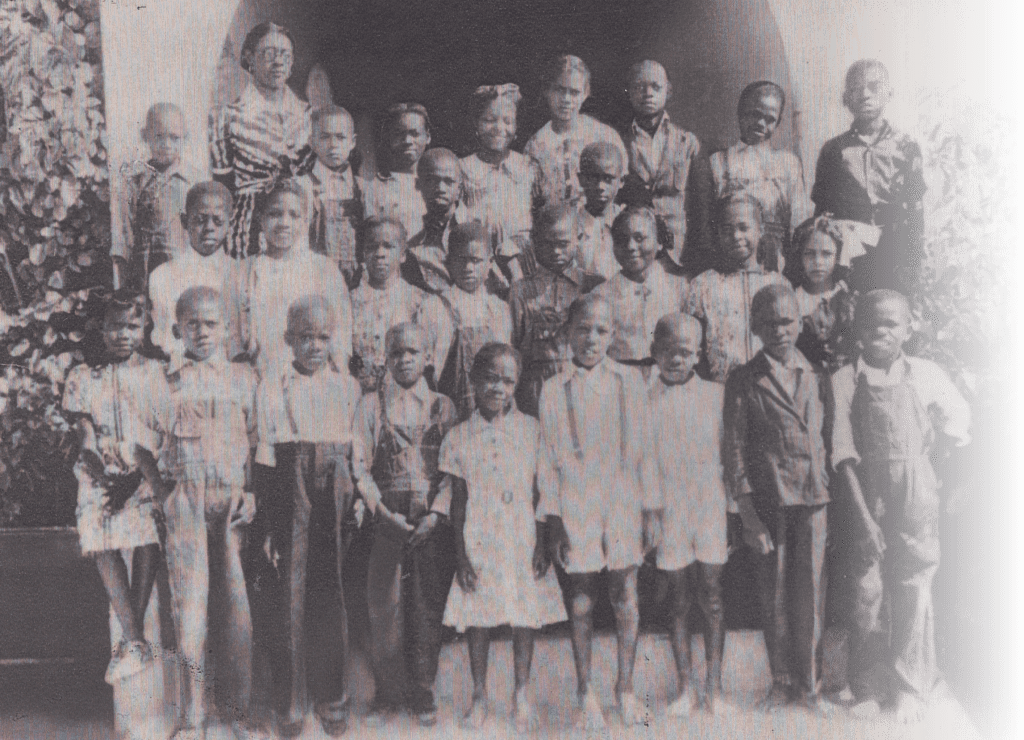

A flood of memories come to mind when members of Deerfield Beach’s black community reminisce about Braithwaite, the all-black elementary and middle school that flourished for over four decades in Deerfield’s predominately agricultural community until Broward schools integrated in 1970.

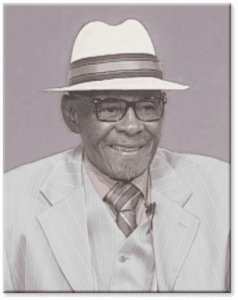

Charlie “Mr. Charlie” Thompson, 90, former head custodian of Deerfield Beach Middle School, shares an impish smile as he remembers the girl who pulled his hat from his head during recess and ran off with it. “I thought she was being mean, but she really liked me,” he said.

Velemina Williams, 82, who retired from Sears, recalled their school books and desks. “They were hand me downs from the other schools. The desks were worn and the school books had marks in them and some of the pages were missing. We never had any new books.”

“We went to school in the summer because the school closed down in the winter during harvest season so the kids could pick beans,” said Leola Brooks, 90, a retired elementary school teacher whose father was a farmer.

While their memories may differ, those who attended Braithwaite speak affectionately of the school. Providing their children an education was first priority with many African American parents. The teachers were well respected and considered family. Lessons were conducted in a disciplined environment, and if a student acted up, he got a whipping with a palmetto frond. When he got home, he got another one. It was a close-knit community and word traveled fast.

“The teachers were strict but very caring,” said Flora Philpart who now works at the Welcome Center at Deerfield Beach High School and attended Braithwaite from 1953 to 1958.

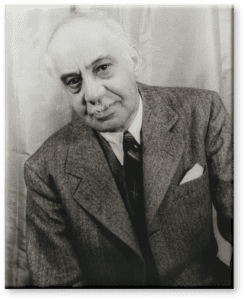

The school was named after William Stanley Beaumont Braithwaite (1878-1962), an acclaimed poet and anthologist. His poetry was recognized in literary circles for much of his life; however, he is best known for his work compiling yearly anthologies of published works in periodicals. These helped launch the careers of many American poets.

Braithwaite replaced Colored School No. 13, which had become too small for the 400 students in attendance.

“It was a grudging gesture to the black community, tolerated as long as most black children could be yanked from classes for months at a time to work the fields,” reported Tao Woolfe in a Sun-Sentinel article dated August 18, 1996.

Broward County School Board records show that a five-acre site in Deerfield was acquired for $500 in 1928. A building was constructed and classes began for hundreds of black students. A school motto was adopted—To educate, to elevate and to cultivate— along with a school song and poem. The school colors were purple and gold.

There were no school buses back then; students walked to school, upwards of a mile and a half. Many came barefooted. Before lessons, they followed a patriotic ritual.

“We had the flag outside where we said the Pledge of Allegiance. Then we went inside and sang, ‘My Country Tis of thee Sweet land of Liberty.’ After that, we prayed. I know I shouldn’t say that, but because of the praying, I think things were better,” said Brooks.

Students who graduated from Braithwaite traveled to Miami, Fort Lauderdale or Delray Beach to go to an all-black high school. In 1970, schools integrated in Broward County and Braithwaite closed. The building was sold to Broward County in 1974 for a health center. It later became Northeast Focal Point Senior Center at 227 N.W. Second St.

Former students raised money to place a plaque at the site to commemorate their beloved school. It is displayed on a bench in the children’s playground.

The Diamond Club

“The thrill is gone. The thrill is gone, baby.”

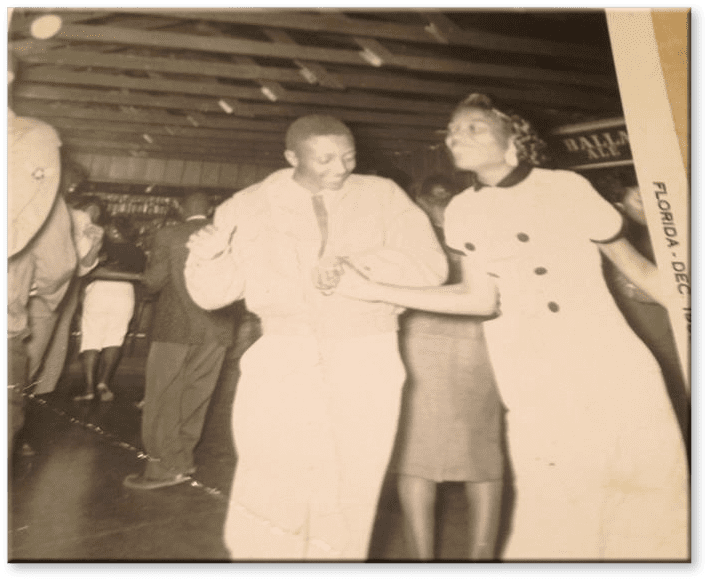

The words from the old BB King song could very well apply to what was once the soul of the black community in Deerfield Beach—The Diamond Club. From the late 1940s to the 1970s, the thumping beat of a drum, pounding keys of a piano and rhythm of guitars wafted through the opened doors of the dance club. Today, however, the epicenter of entertainment for the black community is mostly forgotten.

Located on the west side of Dixie Highway just south of Hillsboro Blvd., the club was historically packed every Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights with young black adults who wanted to listen to some good live music and dance their shoes off.

Willie West, 91, a second generation Deerfield Beach resident, played the piano and sang as a member of the Blue Delrayans who entertained at the club.

“I played there for many years and was the leader of the band,” said West who began his singing career as a young boy belting out blues in the local fields where he picked beans. Later, when he got serious about his singing, he tried to emulate his favorite blues and R&B singers—Junior Parker, Bobby Bland and BB King.

Originally, the club property was a boarding house owned by Robert Bailey Sr. His family lived in the front rooms and rented out the others. Then the facility became a boxing arena. Since there was no ceiling, the ring was open to the elements. A roof was added later and for a short time the building served as a movie theater, which doubled as a community shelter during hurricanes. Eventually a liquor license was obtained and the facility became The Diamond Club.

The building was quite ordinary on the outside, but inside it was a hotbed of rhythm and blues. The bar was located at one end, the band stand at the other and in between a huge dance floor surrounded by tables and chairs, which accommodated upwards of 250 guests. Some of those who entertained at the club included Bull Moose Jackson, Ruth Brown, BB King and James Brown.

“Anybody who was anyone in the entertainment business played at the club,” said Robert Bailey Jr., eldest son of the original owner.

Gwen Major, a retired teacher’s assistant, lived close to the Diamond Club.

“We went to the church right down the street from it, so we never went to the Diamond Club. We heard that people drank there. I did have an uncle who went there. He loved it. He’d come home a little tipsy singing, ‘Well it’s three o’clock in the morning and I’m sitting here waiting for you.’ I remember having to open the door for him in the early morning because my grandmother locked him out because he was late. He said they’d sing and dance and just have a good time,” said Major.

The dance club became one of the most popular South Florida venues for black folks. Many came from as far away as Miami and West Palm Beach to listen to the music and dance the jitter bug, bump ’n’ grind, chicken, twist, hully gully and electric slide.

“They used to have cars parked on Dixie Highway from about two blocks south of Hillsboro Blvd., all the way down to Third St., a long way,” said Thompson. “People would listen to the music and dance and those that didn’t dance would sit around and have a good time. They had fun. It wasn’t wild like it is today.”

In the 1970s, Robert Bailey Sr. turned the club over to his sons Robert, William, Alvin and Adrian. Their cousin Carl Nixon also helped manage the club. With the new managers came a new name—Club Bailey. It operated as a disco and pop music dance club with a DJ and live bands. With the transition, the club opened its doors to everyone.

Club Bailey closed its doors in 1991. The land was subsequently sold to make room for the expansion of Dixie Highway to four lanes.

A Hateful Day

“The thing my father regretted most was the lynching of that man. He grieved the rest of his life because we had no proof, no trial. They just took him and assumed he was the one based on this woman’s word,” said Margaret McDougald Shadoin whose father W.D. McDougald was Deerfield Beach’s first Chief of Police and a sheriff’s deputy.

On a hot July afternoon in 1935, word was out that Marion Jones, a white woman living in Fort Lauderdale, had been assaulted by a black man. Having come to her house for a glass of water, the man followed Jones inside and grabbed her at knife point. As the two struggled, Jones sustained cuts to her hands and arms from the man’s pen knife, but not before her screams and the savviness of her five-year-old son brought neighbors running and sent the man hightailing for his life. An all-points bulletin alerted local law enforcement agencies and residents in Dade and Broward Counties to be on the lookout.

According to Shadoin, Deerfield Beach resident and local farmer Leo Jones was driving north on Dixie Highway in his truck when he noticed a black man stand up, then duck down behind a palmetto. Not recognizing the man, Jones thought it might be the fellow everyone was looking for. He reported the incident to Chief McDougald who immediately called upon several locals to help him search the area. After scouring the woods and coming up empty, the men came to Albert Sample’s house on Dixie Highway.

“Mr. Sample let daddy into the cabins behind his house that were used to accommodate farm laborers in his pineapple fields. But it wasn’t harvest time and the cabins were supposed to be empty,” Shadoin said.

Rubin (also spelled Reuben) Stacey, who was asleep in one of the cabins, was arrested by McDougald and taken to the Deerfield jail. Shadoin recalled that her father informed Broward County Sheriff Walter Clark of Stacey’s capture and immediately transported him to Fort Lauderdale. There Stacey denied he had attacked Jones. Without benefit of a police lineup, Sheriff Clark took Stacey to Jones’ house for identification. The Sunday School teacher confirmed he was the man who had attacked her.

The next day Sheriff Clark heard rumors that a lynch mob was forming and decided to move Stacey to the Dade County jail for his protection. Shadoin recalled that her father, Joe Clark (the sheriff’s brother) and Pop Shulman were called upon to join three other sheriff deputies in the transfer. They never made it to Miami.

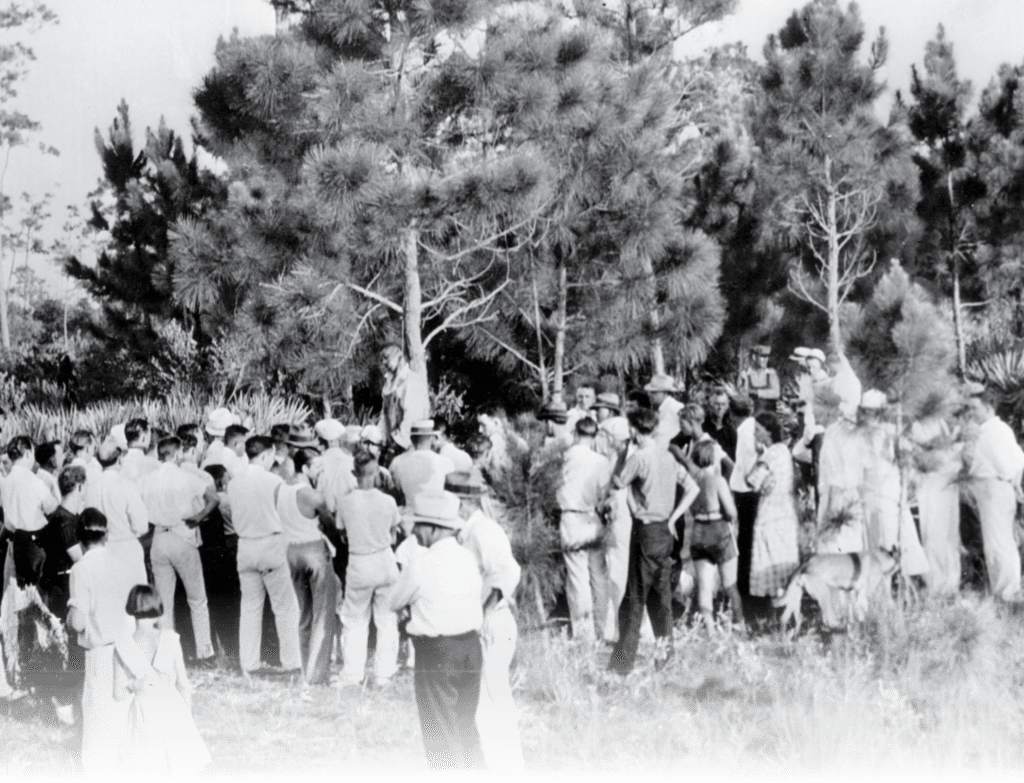

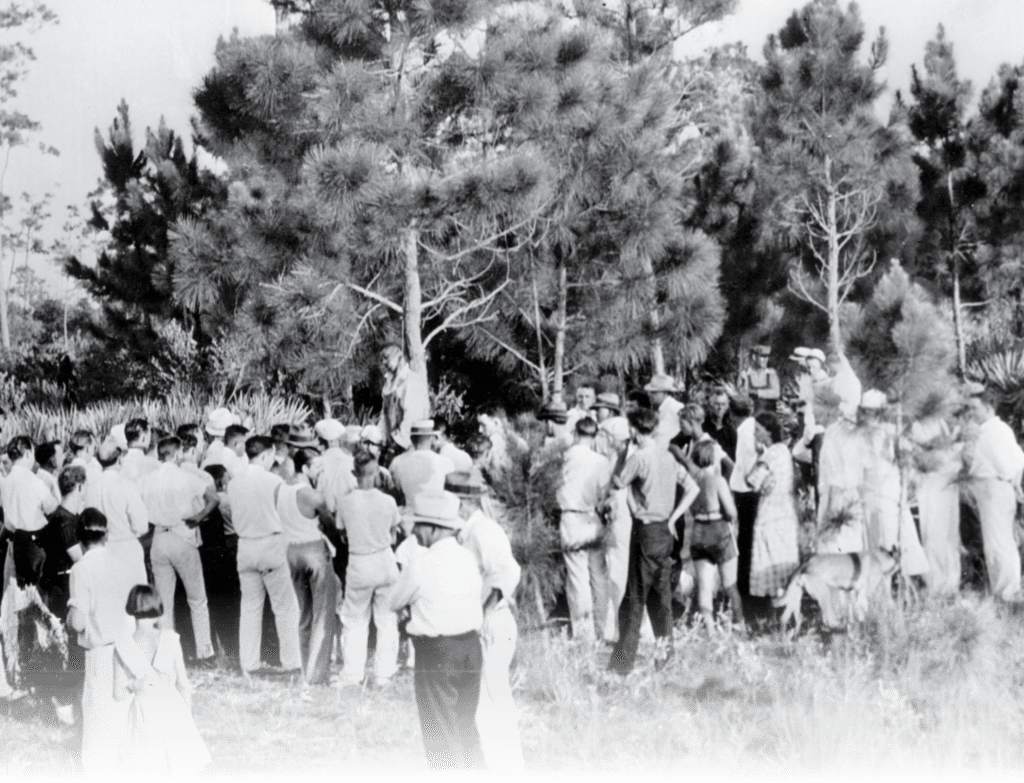

Their vehicle was run off the road and the officers were overpowered by an angry gun-toting mob of, reportedly, between 50 and 100 men. The handcuffed Stacey was pulled from the car, taken into the woods near Jones’ house and hung from a pine tree using clothesline wire, purportedly from Jones’ own clothesline. Several people are said to have shot bullets into his lifeless body. Over the next eight hours, dozens of residents gawked at Stacey’s corpse as it dangled from the pine. A coroner’s inquest was held, but no one was ever indicted. The finding simply stated that Stacey had died at the hands of “a person or persons unknown.”

In 1998, a Sun Sentinel reporter interviewed a woman who claimed to have been one of those who had shot at Stacey’s body. She intimated that Sheriff Clark and his brother had been personally involved in the lynching, maybe even planning it. She further stated that the brothers had killed other black folk over the years. In 1950, the Governor removed Clark as Sheriff. He was indicted on charges of corruption, but was later cleared when key witnesses “couldn’t remember” their initial testimony.

“Of all the things Daddy witnessed, what hurt him the most was that the man didn’t get to go to trial,” said Shadoin.

Numbering 331, Florida ranks fifth in terror lynchings from 1877-1950 and first in lynchings per capita.